On Twins

Some of you reading this will be twins. Most will be fraternal twins. A few of you will be identical twins. You might even be mirror twins–identical siblings who are the mirror images of the other. Around three in every thousand births is a set of twins, so whatever kind of twin you are, you’re incredibly special.

Some of you reading this will be twins. Most will be fraternal twins. A few of you will be identical twins. You might even be mirror twins–identical siblings who are the mirror images of the other. Around three in every thousand births is a set of twins, so whatever kind of twin you are, you’re incredibly special.

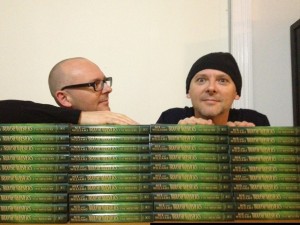

I’m not a twin (I’ve asked my mum a dozen times so I’m pretty sure) but I’ve spent a lot of time writing about them. There’s the Troubletwisters series, co-written with Garth Nix, which follows the magical adventures of fraternal twins Jack and Jaide Shield. There’s my earlier series, the Books of the Cataclysm, about mirror twins Seth and Adrian Castillo. There were even twins in some of the Star Wars novels I wrote. And now there’s my new series Twinmaker, which despite its title doesn’t have any natural twins in the first book, Jump (but there will be in book two).

I say “natural twins” because Jump is about what life would be like in a world where, in theory, anyone could be copied at any time. This is a world where an amazing technology, d-mat, enables anyone to step into a booth in Alice Springs, say, and step out a moment later in Hobart. D-mat works by taking someone apart and scanning them, saving their pattern into computer memory. That pattern is then sent to another booth, where the person is rebuilt from scratch, just like in Star Trek or any number of TV shows and computer games. For someone who travels a lot, it’d be absolutely brilliant, right?

The thing is, once you’ve got a person’s pattern in a computer, what’s to stop you from mucking around with it? You could delete it, for starters. (Would that be the same thing as killing them?) You could copy them, creating a twin of the original. (Would that twin be the same as the original or a different person entirely, as we currently regard identical twins?) Or you could change them in a thousand different ways . . . and here’s where the story of Jump kicks in.

What if someone told you that by carrying a note through d-mat you could change anything about yourself that you didn’t like? You could be smarter, stronger, taller, more beautiful–anything at all. It’s not supposed to be possible, it might even be illegal, but would you be tempted anyway? I know I would be.

Anyway, you can see how this technological kind of twinning would raise all sorts of questions and problems. What if you copied yourself and your copy took over your life? Do copies have souls? If the Pope creates a twin to work as his body double and then the original dies or is killed, does the body double automatically become the Pope? If you have a copy of yourself stored in your computer, can this earlier version of you be used to bring you back from the dead?

Armies of identical ninjas, sports teams composed entirely of one player, famous actors working on dozens of films at once . . . The possibilities are endless. And while it may seem silly to spend time thinking about something that actually isn’t possible right now, these kinds of thought experiments are a fun way to ask how we regard fundamental things like selfhood and identity in everyday life (as philosophers have been doing for thousands of years).

Some people swear that they would never go through such a machine because the person who goes in is destroyed, and the person who comes out is different. In one sense, they’re completely right. In another sense, how is this different from how all the cells in our bodies slowly replace themselves as we grow and age? How is it different from when you go to sleep at night and your sense of self switches off? We feel that we are the same person we were when we were toddlers and looked and behaved very differently, so why wouldn’t we feel the same on the other side of a journey through d-mat, when in theory we were exactly the same?

These are the questions that keep me awake at night–and the concept of twinship lies at the heart of so many of them. Twins have been around as long as humans have been, those rare, wonderful, marvellous people who by their very existence prove just how much the rest of us take for granted in our lives. Sometimes I wish I was one. Other times I’m glad I don’t have to share my birthday cake.

Whichever way I look at it, I know I’m going to be writing about twins for a long time. If only I could create a copy of myself to keep up!

(First published in Reading for Australia in 2013)